The 31st Bienal de São Paulo as a journey

How to learn from things that don’t exist

September, 2 – December, 7, 2014

Curatorial team: Charles Esche, Galit Eilat, Nuria Enguita Mayo, Pablo Lafuente and Oren Sagiv

Associate curators: Benjamin Seroussi and Luiza Proença

Curatorial concepts

Perhaps the best way to understand the current status of the 31st Bienal de São Paulo is to think of it as a journey. The route the Bienal team has followed takes in well-trodden paths, backyards and dead ends and involves some lost and found baggage, as well as many new thoughts that have sprung up on the road. This journey is, of course, not yet at its end – that will only be in December 2014 – yet this idea of journeying is one we would like to offer those visiting the Bienal after it opens on 6 September. There will be many opportunities to understand the nature of the journeys, shaped by densities of different artworks that will add up to a set of itineraries around a common idea. There will be conflicts, discoveries and transformations through projects developed by artists, sometimes in collaboration with others.

From the beginning we wanted to work together as a collective body and, though it took time to build, we believe this is a methodology more attuned to our precarious contemporaneity (as we can see in the streets everywhere). The device of the journey is an attempt to look at the world and its art from the perspective of Sao Paulo, travelling out from here to the world. Tentatively we sense, not only here but in different societies across the globe, that people are poised in a precarious balance between hope that new and imaginable social possibilities might be opening up before them, and a fear that there can be no change in the current global system outside its existing rules and controls. The projects we have invited to the Bienal seem to us in their different ways to address this ambiguity in society and to suggest ways by which it might be talked about, learnt from, struggled with or used to help shape our (cultural) future.

Journeys

The journey started in at least three very different directions. One was to delve into the history of the Bienal de São Paulo and the Ciccillo Matarazzo pavilion, where the exhibition has been located since 1957. The other was to travel out into Brazil and the present state of its artistic, cultural and political scene, considering it in intense relation to a wider Latin American context. The third was to engage in a conversation and exchange with the permanent teams of the Bienal, its supporters and the wider world around us.

Our initial actions were to organise ‘open meetings’ across Brazil in collaboration with local institutions and people. The meetings, in cities such as Porto Alegre in the South, Fortaleza, Recife and Salvador in the North East, Belo Horizonte and São Paulo in the South East, and Belém in the North, allowed us to set up a situation of exchange through which to hear about local artistic perspectives, interests, concerns and urgencies. We touched on issues of art and its relationship to life in the cities; we spoke about education and cultural infrastructure, local social dynamics and current political struggles among much else. All this information has been fundamental to how our curating has developed. The meetings, besides initiating relations that have continued since, revealed that the art scene in Brazil is broadly anchored yet very different from city to city and region to region, and that the communication between the different locations is not necessarily always equal or satisfactory. We could also observe differences in the type of work made in different cities, often depending on the presence or absence of a functioning art infrastructures and art market, as well as the different relations art establishes to wider cultural, social and political context. Travelling through Brazil and other parts of Latin America, the movement of people, their displacement and resettlement became a major concern – from the right to free, or even affordable, public transport to the experience of migration and the social invisibility of nomadic groups as well as attempts to establish interlocution with indigenous peoples.

At the same time as this geographic journey, we began to analyse how the Bienal pavilion itself – the iconic symbol of the event – has been used in the past. Our studies of past Bienal architecture and of the raw building itself revealed unique and diverse architectural qualities that can be used to enable different types of encounter with artworks and the idea of art. We will try to take advantage of these characteristics in the ways works and projects are displayed in order to emphasise the bodily act of being in a Bienal event and the transformative potential that it holds for users of the space. This will mean allocating different functions to different spaces, not treating the pavilion only as a container for art, but as a space for its anticipated 500,000 users, their needs and comforts.

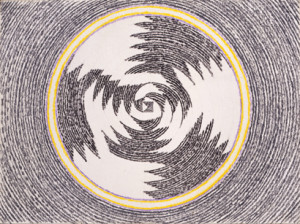

These journeys, through Brazil and into the building, began to inform what we thought might be relevant or appropriate for the event. One of the first artists to make sense to us was Prabhakar Pachpute. His ability to create images that communicate with an organic intensity led us to invite him to take part in the design of the 31stBienal’s visual identity – a four-month process with the Bienal’s design team that had been built around the notions of imagination, transformation, collectivity and conflict. The image we chose, a monstrous form without vision, walking uncertainly but with determined desire as a collective body, sharing a common intelligence and expanded sensoriality carries those four ideas that have become crucial to our work. They have already been the basis of our education materials, produced in February to allow teachers to apply them as tools to prepare the ground for school visits to the Bienal in the spring.

Imagination and transformation

To address the journey through artworks, we turned to an epic traveller of art, Juan Downey, a Chilean who made works across the Americas, creating a singular relationship with the indigenous communities he sought out, and questioning the codes according to which people are (re)presented. We engaged in a conversation with Romy Pocztaruk, an artist whose photographic exploration of the Transamazonas and the abandoned town of Fordlândia shed a new light on these ‘forgotten’ territories; and with Danica Dakic, who has made work with populations in Europe that are not granted the rights or access that ‘normal’ citizens enjoy. Also Armando Queiroz’s work on and about Amazonia has addressed the invisibility and the ongoing violent disappearance of the indigenous people of Brazil.

Such modes of existence relate directly to the one fixed element in our otherwise shifting exhibition title: the things that don’t exist. Our title poses several, different ways of addressing these things: how to talk about them, how to learn from them, how to live with them, how to struggle with them… in an attempt to point at one of the main capabilities of art – to make visible what is unseen, to conjure things into being, and to effectively shift the relationships that constitute our world. The paintings of Jo Baer, where she struggles to interpret the whirlwind of thoughts that emerge from the ancient and silent standing stones of Ireland, touch directly on this. Val del Omar transforms the inanimate Baroque statues and Arabic architecture into living creatures full of a mystical energy and threat (mixing mechanics, optics, poetry and mysticism). Asger Jorn also works in a similar direction with his photographic project devoted to the symbolism of sculpture and architecture in a Northern European context. Others, like Sheela Gowda, Tunga and Lia Rodrigues or Edward Krasinski, enact a more material transformation that shifts the nature of ‘matter’ so that its shadowy, magical, alchemic properties can emerge and allow for an experience that transcends the conditions we inhabit.

The concept of non-existence can equally be read as the result of our narrow political and economic imagination. Most of us live in a world where the dominant ideology, neo-liberal capitalism, seems able to ignore or exclude inconvenient experiences or life forms from their consciousness, or to incorporate them in a manner that betrays the principles and nature of the things to such an extent that they no longer retain any of their original character. This process makes certain kinds of emotions, beliefs and encounters unreal, because the languages that we need to share things with others are not able to account for them. On occasion it might seem as though the things themselves never happened and their memory is quietly put away. Bringing unarticulated things to attention is one of the tasks we have set ourselves for this Bienal, and art’s political capability today may partly lie in awakening things that do not or cannot exist in the current consensus and giving them new purchase on the world, sometimes by simply recognising that they are absent. Walid Raad’s gentle considerations of the cognitive disapperance of artworks touch directly on this feeling, as do the semi-documentary narrative installations of Basel Abbas and Ruane Abou-Rahme in a different register. The textiles by Teresa Lanceta are made after sharing some time together with nomadic Berbers in Morocco, allowing her to put on show a collective way of life and a common knowledge that is vanishing under the threat of the global market and mass tourism.

Art can also be a disruptive force. It can account for the appearance and behavior of people and the world in ways that are negative or provocative. Art can create situations where the disallowed is recognised and valued. This is the condition we call the trans-, representing transgression, transcendence, translation, transgender, transit, transsexuality and transformation amongst others. Such crossing of borders (a crossing that might also be part of a journey) can happen through literal bodily (gender) change or different mental states (systems of belief): sometimes, even often, they come together. The films of Virginia de Medeiros, Nurit Sharett and Yael Bartana, as well as the mysticism of many of the artists above capture this sense of the trans- and put it into effect.

Education

One of the affects of the trans- is that it is no longer possible to return back to the original or, said differently, you can’t put the paint back in the tube once it is out. The trans- implies a change of state such as that which occurs in successful educational encounters. From the Fundação Bienal, we have had the chance to collaborate with an Education team that has been working for over 4 years under the direction of Stela Barbieri. The experience and knowledge of this team, including its networks into schools, communities and local organisations have served as a basis for the curators to start inviting artists who would be able to rise to the challenge of collaboration and collective work. The partnership with Residência Artística FAAP has also allowed several artists to stay for lengthy periods of time and experience different sides of São Paulo and Brazil. The Education team has been assisting these artists with their research, helping them shape the creation of new works for the Bienal, as the São Paulo team’s insights and concerns combine with the artists’ initial ideas. In this way, the preparation of the event’s mediation and questions about how to address and exchange with the public is present from the very beginning of the process.

A concern with education will not seem strange in Brazil, a country with an extensive history of radical education and with an urgent contemporary issue of spreading and upgrading mass learning. Many attempts here and elsewhere have been made, at a large and small scale, to change social structures and address inequalities through education, and for the 31st Bienal we have invited a number of projects that look through the history of experimental education to see how we might reevaluate its potential today. Pedro G. Romero is researching the Modern School’s aesthetic and political consequences, while Imogen Stidworthy is working with the legacy of Fernand Deligny in Monoblet, France; Graziela Kunsch and Lilian Kelian will think about the past and present of the education system in São Paulo and Brazil. All are proposing questions and models that will inform activities throughout the exhibition. In this way, we want to put education and the users of the 31st Bienal – schoolchildren, students, communities and visitors – at the centre of the action. Besides working with artists deeply engaged in these questions, it means dedicating space in the pavilion not only to art but also to the act of welcoming, preparing, talking and thinking. Fortunately, the building’s architecture is ready for such an intervention, with a ground floor that opens directly onto the park and offers an intermediate zone between man-made nature and the enclosures needed for showing certain kinds of art. In order to create this transition, the conception of the space is being developed in collaboration with artists’ groups with experience and investment in these issues, such as Contrafilé and Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti.

Our concern with education also operates in a smaller, almost intimate scale, with the construction of a three-week workshop titled Toolbox for Cultural Organisation. For three separate weeks over a 10 month period, a group of 17 invited young artists, curators, writers and cultural activists are engaging in theoretical and practical discussions with the curatorial team and other guests, aiming to address how to work in culture today. The intention is to offer tools that can contribute to the transformation of the places and institutions where the participants live and work.

Conflict and collectivity

Working together, horizontally, and working within situations of conflict, seem to us fundamental attitudes today, especially in a country and world that are going through significant social change. While the divide between rich and poor is becoming bigger every day, there seems to be few means to address this with the artistic tools we currently have. Cities and regions are radically changing, yet the mechanisms of political representation offer few holistic responses. The speed and direction of travel are producing conflicts across the world, and it is not too difficult to foresee a crisis of political representation, where a growing cry of ‘not this way!’ is accompanied by the urge to stand together and oppose collectively what are patently unjust situations. This intimate connection between conflict and collectivity is something that is often a source of energy and inspiration for artists.

Some, such as Ana Lira or Halil Altindere, have turned their camera on the recent struggles, one recording the disappearance of the image and slogans on political posters in Recife, the other working with young men from the Istanbul suburbs to voice and act their anger (and joy) in song. On other occasions, participating artists merge ideas and concerns from their own locations with conditions and people they have encountered in Brazil. Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa will restage what Pier Paolo Pasolini left out of his version of Saint Mark’s Gospel with the help of amateur actors from several areas of São Paulo; Etcétera… will propose a political theatre with the help of Léon Ferrari; Yochai Avrahami is taking the displays of historical museums in Brazil as a starting point for a narrative told by and through objects; Ines Doujak and John Barker are investigating how textiles are the basis for a system of exploitation and how they might work, here, as tools for subverting such system.

All these projects, and many more, will be assembled in the Bienal pavilion in a series of densities, some intense, some relaxed, that tell stories about things that do not exist. Our many users will fill the space and perhaps appropriately create images of bodies together, huddled, proud, embracing or clinging to each other in order to complete our journey. The films and paintings of Leigh Orpaz and Bruno Pacheco as well as the drawings of Prabhakar Pachpute might be accurate images of the likely experience of visiting the Bienal, but they are also relevant as a way of considering how those things that don’t exist might be called into existence. It is by acting in common, in this case around art, and by sharing ambitions and values opposed by the dominant system, that we might together achieve a transformation towards a different way of seeing things, of talking about things, of fighting about and against things, and transforming ourselves and our relation to the world around us.

Text: 31st Bienal’s curatorial team

Image: Juan Downey, WAYU, 1977