8th Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art (GIBCA)

September 12 – November 22, 2015

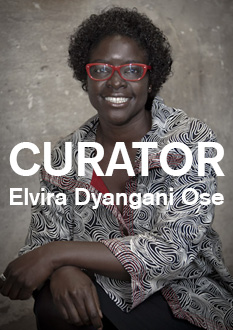

Curator: Elvira Dyangani Ose

In conversation with GIBCA Elvira Dyngani Ose talks about her impressions of Sweden, its art scene and the questions that she thinks will be central to GIBCA 2015.

GIBCA: On the 24th of September 2014, the Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art (GIBCA) team had the great pleasure of introducing you as curator of GIBCA 2015 at a launch event at Röda Sten Konsthall. There you had the opportunity, for the first time, to talk to the public about your ideas for the upcoming edition of the Biennial, including the complex notion of “history writing” which GIBCA 2015 will focus on. Why do you want to challenge and explore the notion of “history writing”?

Elvira Dyangani Ose: I have always assured my commitment to artists and artworks that inscribe certain events, individuals and communities into history. In the cases that I consider most successful and daring, the emphasis is on more than just the presentation of legitimate evidence of such episodes and its protagonists. Rather, the emphasis is on questioning the systems of power that effectively silence, marginalize and remove certain individuals, communities and events from the historical equation in the first place.

Being myself part of such community – as a Black scholar and curator, post-colonial subject and African – made me fully aware, at a certain point in my career, of the power implicit in this binary narrative and the nature of some institutions able to consolidate that power. It was in arts and culture (and in particular in the work of modern and contemporary artists, writers, thinkers and performers from Africa and its Diaspora) that I found poetical and political responses to some of the concerns I had as a human being. Then, my focus was to transform that Blackness, African-ness and post-colonial character – like some of these practitioners have done – into decisive tools to engage with the world at large: challenging that labeling, re-appropriating it and building on a certain notion of togetherness that subvert the us-and-them rhetoric. And it is from the vantage point of this togetherness, from the desire of imagining history as a participatory experience, that I would like for GIBCA 2015 to explore and challenge history writing.

A direct inspiration for this focus is the Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot, who claims that there are many participants alongside professional historians that can affect history and its production. With time one realizes that – as Trouillot urges us – in order to add complexity to history-making or to affect change, if that is even possible, one needs to call into question the narrative that excludes those communities from history in the first place; in sum, the production of history itself.

GIBCA: You are also inspired by the Italian writer, philosopher and historian Umberto Eco’s notion ofthe open work and how that possibly can be used as a tool or methodology in the writing of history. What potential do you see in Eco’s concept?

Elvira Dyangani Ose: Umberto Eco’s poetics of the open work offers an incredible opportunity to rethink history as a participatory experience. The notion of open work appears for the first time in 1962 in Eco’s readings of the works of musical composer Lucio Berio, artist Alexander Calder and writer Stephane Mallarmé. In Eco’s own words, all these works contain a halo of indefiniteness, a sense of incomplete order, offered to the musician, viewer and reader, respectively, to complete. If one follows Eco’s notion and sees history from the perspective of something being constantly in motion, forever open and always promising future perceptions, one can establish a radical and transformative relationship between the nature of history and our role as narrators and actors in the production of such history. The Biennial will aim to radically change the nature of the relationship between the artists and their publics, demanding from the latter a higher degree of awareness and collaboration. GIBCA 2015 will takes Eco’s notion of open work as both a conceptual backdrop and curatorial methodology, inviting artists, thinkers and cultural producers, together with members of civil society and public authority – from Scandinavia and across the globe – to partake in various initiatives inquiring the meaning and production of history.

GIBCA: In addition to these ideas by Eco and Trouillot which have influenced your curatorial approach, what central questions do you want to raise with the Biennale?

Elvira Dyangani Ose: The first question is whether or not we, as individuals and communities, are capable of affecting change in history-making at all. And, if given that opportunity, what will we do? Can we simply make up the past according to our own convenience? Who or what would then be the collective subject of history?

Once we have accepted the responsibility of being public intellectuals, narrators of history-making, how do we make what is fundamental to the local relevant to the universal? How do we inscribe into history the collective memories, personal narratives, inner worlds, stories and protagonists located within the margins of such history? Can those strategies, which are situated within the boundaries of storytelling, challenge and affect history-telling?

Another concern is if this reconstruction of the past can ever challenge current historiography and its methods of inclusion and omission. And, if so, what may such an attempt add to future processes of history-making? In this sense, current affairs and “the present” will function as fabulous fieldwork.

The key will ultimately be for GIBCA 2015 to display projects that don’t necessarily provide responses to these questions, but rather dissent from them. The projects involved will pose more questions and make evident the problematic of a linear narrative that not so long ago was set to be truthful and complete.

GIBCA: You recently spent almost three weeks travelling in Scandinavia visiting Gothenburg, Stockholm, Umeå, Malmö and even Copenhagen to meet a wide range of artists and art professionals. What general impressions do you have from your trip? Can you elaborate on some of your reflections?

Elvira Dyangani Ose: To a certain extent, I wish GIBCA 2015 was a Nordic Biennial! I met such a fascinating, engaged and insightful group of artists across generations, cultural backgrounds and media, that I could envision such a kind of show right away. For better or worse, however, this is an international Biennial and I won’t be able to invite many of them. Likewise, my conversations with colleagues in government and non-government organizations, including cultural producers, activists, historians, architects, musicians, writers, filmmakers, university professors and scientists, have been incredibly rich and fruitful.

Sweden is in a crucial moment of its contemporary history with regards to politics and its impact on society and culture. Given the current political changes, recent social turmoil in response to financial strategies, review of the Swedish model and enquiry into notions of public-ness, to question history-making is especially critical to Sweden right now, and Scandinavia at large. The Biennial presents itself as a desirable and neutral platform for some of these conversations to take place.

I love working horizontally in a collaborative fashion, and if we truly want GIBCA 2015 to imagine history as a participatory experience, the structure of the Biennial has to be a collaborative one. I genuinely hope some of the conversations I have had will materialize into projects, programs and experiences engaging both this variety of professionals and also the general public.

GIBCA: At Valand Academy in Gothenburg and a recent Iaspis/Konstnärsnämnden public program in Stockholm, you gave a lecture called “The Artists as Intellectual”, which was based on an analysis of the artistic practice of American artist Carrie Mae Weems. For those who could not be present, can you briefly account for the scope of this lecture?

Elvira Dyangani Ose: I met Carrie Mae Weems in New York in 2007 at the event Here and Now: African and African American Art and Film Conference at New York University organized by artist and professor Deborah Willis. At the time I was a great admirer of Weems’s seminal works, such as Coloured People (1989-1990), The Kitchen Table Series (1990) and From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995–1996), but I had never met the artist. I saw Weems wandering in one of the rooms of the Whitney after her talk and I got up the courage to introduce myself and mention on the spot that I wanted to work with her in a large-scale exhibition. At that time, I had decided to pursue my doctoral studies at Cornell University in New York, and we developed a fabulous friendship within a generous mentorship scheme that eventually produced the exhibition Carrie Mae Weems: Social Studies at the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo in Seville, Spain in 2010.

The title and concept of the exhibition Social Studies referenced the artist collective with the same name that Weems founded together with Deborah Willis, Dawoud Bey and Lonnie Graham in 2002, as well as Weems’s own practice invested in the revision of history, the appropriation of collective imagery and the inversion of stereotypes deriving from such imagery. Essential series from the previous twenty-five years of Weems’s career were featured, through which the exhibition explored the role of “artist as intellectual” in culture and history-making. My curatorial approach was inspired by readings of Antonio Gramsci’s concepts of traditional and organic intellectuals, Grant Farred’s formulation of the vernacular intellectual, and Carole Boyce-Davies’s category of the radical transformative intellectual.

My presentations in Gothenburg and Stockholm drew from a reformulation of the figure of the public intellectual and presented works where Weems explores photography as performance and re-enactment, discusses and inverts artistic canons, and observes disciplines such as architecture to reflect on its symbolic character and use as a representation of power. Within all of these approaches the artist pays special attention to the codes of cultural, gender and class identity occurring in both the private and public spheres.

GIBCA: What particular thoughts lie behind the use of this term “public intellectual”, and how do you imagine it coming into play for GIBCA 2015?

Elvira Dyangani Ose: A public intellectual has social responsibilities. He or she may embody Gramsci’s organic intellectual, who emerges from within the group as an emancipated and outspoken man or woman – an elite whose future is devoted to the creation, maintenance and evolution of their group ideology. Or one may follow Grant Farred’s vernacular intellectual, who resists, subverts or impacts the dominant discourse by embodying local thought and popular culture. Lastly, you could represent Carole Boyce-Davies’s notion of a radically transformative intellectual, whose practice is organized around the production of knowledge directed at transforming the social contexts in which you live and operate, both in and out of academia.

The majority of the artists, cultural producers, thinkers and many other guests involved in GIBCA 2015 embody, has embodied, or will potentially embody the role of public intellectual at some point in their career. Indeed, the possibility of becoming a public intellectual exists for all of us, providing that the right set of circumstances are established, and most importantly, that we find within ourselves the audacity to accept the challenge.

Image Courtesy Göteborg International Biennial.